I’m shutting my startup down after 4.5 years - here’s where I went wrong & why

tl;dr

We're shutting down Advisable.

After launching an initially successful but problematic version one, we relaunched with a new approach that we felt had the potential to solve the problems of our first version.

However, after 3 relaunch attempts, we haven't been able to get this new version working well enough to be investible or profitable. So we're shutting down.

The underyling reason for this failure may be because, while what we're doing intellectually made sense, we're trying to build a revolutionary product and we're not the people we're building for nor do we deeply understand them.

However, it may also just be that we're in a bad market, we executed poorly, or any other number of reasons - more on all of this below.

In any case, we're shutting down. If you're looking for incredible engineers, operators and designers to hire, some of our team are looking for new opportunities. You can learn about why I think they're so great here.

We've decided to shut down Advisable.

Rather than quitting quietly, I've decided to do the exact opposite: to try and explain why exactly we failed and the mistakes that I made - even the deep & painful ones - and to share this in the hope that it might help others! Doing this also has the benefit of forcing me to confront everything and build a coherent, satisfying explanation for myself.

However, one major caveat is that, as with any telling of the past, it has the potential for hindsight bias, inaccurate remembrance, and more. While I am a bit negative towards my past self, I think it's mostly accurate, and, for stuff from the past, what I say lines up with my writing elsewhere - in investor updates, personal notes, etc.

Another thing to keep in mind is that it’s actually very hard to determine what actually caused what. I think there's a natural desire to explain things in a simplistic manner but Advisable, like most businesses, failed for many reasons - all intertwining and interacting in different ways. As such, I think there's a limited amount we can learn from any individual explanation - so I've tried to include a bunch of different explanations where appropriate in order of the likelihood that they were critical.

With this in mind, If anything doesn't make sense to you, if you need further depth on any point, or if you feel that I missed or underestimated something, I'd really appreciate you letting me know via email.

Why I started Advisable

A vision based on my own experience, or arrogant self-deception?

In writing this section, I'm going to try to intertwine 2 perspectives - first, the perspective I had at the time, which in my view now was fairly arrogant and self-deceptive, and second, my perspective now, which is pretty cynical about my old self's motives but hopefully honest.

You can make up your mind on who to believe but one thing neither of us would disagree on was the fact that one of my primary motivations in starting Advisable was my love of startups.

I was lucky enough to have gotten to see the best in startups early in my career - the ambition, the creativity, the impact - and I really wanted to create one of my own.

"Past me" would've said that this was a secondary motivator and that the primary one was me wanting to build a product for people like me.

It is true that I had experienced the pain of my problem first-hand - having both been a marketing freelancer and having hired other marketing freelancers.

And yes, I did legitimately believe (and still do!) that the existing freelance marketplaces are terrible, dehumanizing experiences for both companies and talent. It's a very broken space full of bad products - probably ultimately why there's never been a great business in the space, only a bunch of mediocre ones.

However, while it is broken, was I truly trying to build something better for people like me? Did I have a distinct, compelling vision for how exactly it could be better? Was I doing this because I thought this could be a great business?

Honestly, no.

Looking back, it feels as though I had a startup-shaped hole in my life and this idea roughly fitted in: there were kinda successful businesses in similar spaces, I knew how to get a basic version working quickly, and I felt as though I seemed like the kind of person who could credibly do it.

However, most of the reasons I told myself why I was the person to do this were shallow - for example, I had told myself that I, as a former marketer, was well-equipped to start in this space due to my passion for it. However, while I had been working in marketing, I actually had very little in common with a 'traditional' marketing type. I was more of a systems thinker and builder who happened to build stuff for marketing, but I didn't really care about most of what was important to other marketers.

Did I think that this would be a great business? At the time, yes, but this was mostly based on me thinking that - thanks to my unmitigated brilliance - I could overcome all the issues that had hampered hundreds or thousands of other founders in the space and had prevented them from building great businesses.

However, what I did have was the knowledge that I could get the first version of this working. I knew how all the pieces would fit together - all I'd have to do was assemble them.

This gave me the confidence to embark on the journey, even though - had I been honest with myself - I would've admitted that I didn't really know where I wanted this journey to lead beyond the start!

Our first version

The first step on the road to greatness, or adhering to the status-quo due to a lack of a compelling vision?

How did our first version work? Why did we do it this way?

Our first version, roughly speaking, followed the status-quo in our space: companies would post jobs, and people would apply to them.

We did it this way because this was how job postings worked for full-time roles, and was therefore what clients were comfortable with for freelancer roles. This is why others like Toptal, Upwork, etc. also function this way.

While the job application experience isn't ideal in many ways, we felt that we could automate lots of stuff behind the scenes to make it a dramatically better experience for both clients and talent.

For example, instead of having to sift through 10s or 100s of applications, we'd automatically select the top candidates for a role, invite them, and only present the best applicants to clients - saving them lots of time.

For candidates, instead of them having to go through every role on our site to find ones to apply for and compete with 100s of others, we'd automatically share the ones that were highly relevant for them, and they'd apply and only compete with a few other highly relevant people.

We felt that we could refine and automate this system to the point that it was a smooth, consistent experience for both clients and talent, and far better than what existed before.

In what ways did it work?

While it wasn't exactly a slick experience for either party and required a lot of manual effort from us to deliver, we were able to get this working, and it actually was a decent service!

Here were some of the ways in which our first version really worked - you can click on each one to get more detail:

Clients were able to request any specific kind of talent and we could mostly deliver!

Clients were able to come to us with any kind of specific requirements, we were able to provide them with a range of high-quality options within 1-2 days.

We were pretty good at sourcing people with highly specific skill sets, vetting them, and pitching them to clients - all mostly automated or streamlined through a variety of clever processes.

The quality of talent was good enough that some clients hired up to 10 people

The talent we provided was good enough that many people came back to hire again and again, with some like Stack Overflow hiring up to 10 people from us!

We were so confident in our recommendations that we could offer a money-back guarantee

We offered a money-back guarantee on the first chunk of work that the freelancer completed and rarely had to pay out.

When it worked for freelancers, it could work really well

We had a bunch of people who earned over $50,000 from their work with us - people who’d be hired 5+ times from various clients - and some who'd earned over $100,000!

It worked so well for some that they quit their full-time jobs to work with clients they met!

For some freelancers, it actually had a transformative impact on their lives, with at least one person quitting their full-time jobs to freelance full-time, thanks to the clients they discovered through Advisable

We had good growth and were almost profitable one month!

We grew our bookings by almost 30% for 6 months straight, leading to one month of almost being profitable! The fundamental economics of the business weren't unworkable.

In what ways did it not work?

While the service fundamentally worked, there were (self-evidently!) a bunch of ways in which it was far from ideal:

When you're a platform for specific talent, people mostly looking for people to do highly-spec'd work

First of all, one fundamental issue with this kind of platform is that - if you’re a platform offering specific talent - people tend to come looking for talent that they need for a highly-specific purpose.

This is good in some ways - the people have strong hiring intent when they find someone - but also bad in others. For example, one consequence is that most of the work posted to the platform was very specific and granular - if they were hiring a content person, the brief tended to be closer to “write a blog about this specific topic that covers these points” than “figure out how to write a great piece that addressed this topic” - more low-level and specific.

They mostly only came to us when they knew exactly what they wanted.

The requirements were so specific that we needed account managers to select the talent we recommended to clients

Another issue is that, by the time someone posted a job, they tended to have a highly-specific idea of the person they were looking for.

This meant that in order for us to pick and match a candidate to them, the person needed to fit exactly their requirements - this could be a combination of their skillset, industry experience, interests, location, and more.

While we could do this, in order to deliver to the level of specificity that they required, we needed to expend significant manual effort. This meant that - even with all of our automation - for every 20-30 hires made per month through the platform, we’d need an account manager to help the clients make their selections and manage the process.

The account managers needed to be knowledgeable and highly skilled to make good recommendations

Because the account manager was advising on complicated hires, they needed to really understand the client and industry.

They couldn't just be new grads or interns - they needed to really know what they were talking about.

We needed to have a human-driven approach to build up client confidence in our recommendations

Not only did we need to have human input to select the candidates, but we also needed to have people on calls with the clients to build up their confidence in the recommendations that we made.

If we didn't do calls, they didn't trust the recommendations enough to commit to them.

We needed to ask for a deposit to get commitment from clients

Given the cost of our recruitment process, when a client didn't continue, it was very bad for us - we expended a lot of effort and cost for nothing.

In order to combat this, we needed to ask clients for a $500 deposit to get them to commit to the hiring process.

This worked but acted as a deterrent for many clients.

We needed to get a lot of applications from freelancers to get enough good recommendations for clients

In order to deliver this perfect match, we needed to invite a higher number of candidates than we’d ideally like - so we ended up having to invite 40-50 people to a job, of which 15-20 would apply, of which only 1 would usually get hired.

This meant that - even though we tried to make it better - it was still a fundamentally bruising experience for most talent with a very low success rate - less than 5% of applications resulted in a hire.

We couldn’t automate their applications to save them this rejection due to how specific the client requirements were - when we automated stuff to this degree, the quality of the experience for clients degraded significantly.

The quality of talent and work was often unpredictable

Even with many applicants to choose from and a human-driven recruitment process, the quality of the talent and work was often unpredictable. This could be due to anything from dubious credentials, to the freelancer being distracted, to all kinds of random things.

When you have a human element in your product, things just go wrong in weird and unusual ways.

And many great people won't apply for a job in the first place

Regardless of how slick the process was, and how good their odds of success are, many great people just simply won't apply for a job.

This is especially true for highly-in-demand people, who have many clients waiting to work with them - often the case for the best talent.

Our second version

Recognising that we were on the path to mediocrity and taking action to try to reinvent how the space works.

Why did we go for a radical change?

We felt that the issues we experienced were endemic to our approach - we wouldn't be able to solve them with more incremental improvements. This is why these issues are mostly shared by all the other players in our space.

As a result, we decided to radically change what we did - to try to build something that had the potential to revolutionise how our space worked and be fundamentally better than what existed before.

While we did this for a bunch of reasons, they all ultimately come down to the same thing - with our previous approach, everything from our service to clients, to how we treated freelancers, to our product experience, would be inherently mediocre at best.

Not only would it not have been an exceptional service for anyone, it felt like - in a space where there’s never been a truly great business - this definitely wouldn't have been one either.

While we did a bunch of stuff very well, we weren’t doing anything fundamentally different from what had led to the mediocrity of our predecessors.

We’d created an okay service, with an okay product that, in the very best case, would’ve been an okay business.

We would never have been great by any meaningful metric.

How did our new version work? Why did we do it this way?

So, we decided to try to fundamentally rethink how everything worked!

We wanted what we’re building to be the place that actually helps clients and freelancers form high-quality collaborative relationships - the kind of relationships that result in great work that’s fulfilling and impactful for both parties.

To do this, we looked to different places where people actually built these kinds of relationships today. These weren't freelance marketplaces or job sites - but rather, places like Twitter, Dribbble, and Github where people showcased their work to be discovered by others.

While their primary goal of sharing work isn’t necessarily hiring, many people discover their work through them and want to hire them based on it.

Because they 'discover' them in a serendipitous, organic way, the relationships formed tend to be a lot more natural and organic, and result in more high-level work than the ones on freelancer platforms. They tend to be more collaborations between peers, than the dictatorial hiring manager/freelancer relationships.

We wanted to capture what works about the dynamics of these 'organic' platforms into the model of a freelance marketplace - with a product that allows freelancers to share their best work, and clients to discover these freelancers based on it.

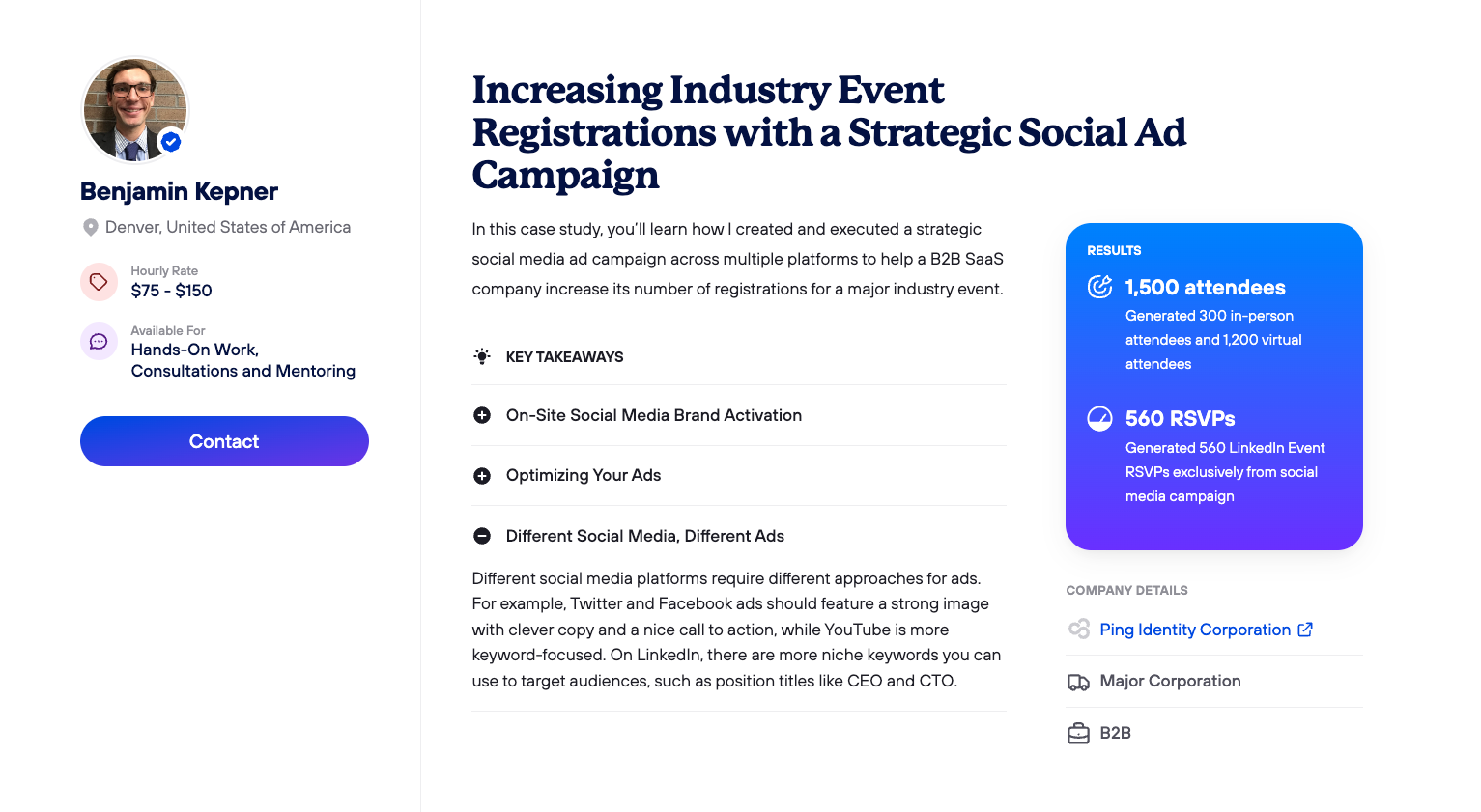

Freelancers could create case studies of their work:

And then clients could explore these projects:

They could learn from the freelancer's hard-won insights and learnings:

And hopefully, when learning and getting ideas, the clients would be inspired to do new projects or up their game on existing ones - and would then reach out to the freelancer to help them with advice, mentorship, or hands-on support:

If they wanted to work together, we'd then manage all the bookings and payments and make it easy for them to collaborate without worrying about billing, admin, contracts, or any of that annoying stuff.

Why could this approach have solved the problems in our space, and also have worked at scale?

We felt that this approach could've solved so many of the problems that have haunted our space and, in theory, at least, delivered a better solution than anything that existed today:

We could equip clients to make decisions for themselves - with a fun discovery and learning experience.

First of all, instead of us having to basically make the decision on behalf of the client, we would equip the clients with the information they needed to make the decision themselves.

We wanted to make this into a fun discovery process that people would enjoy independently of needing to discover talent - so they’d find talent they want to hire while browsing and learning.

Our hope was that this meant that, because clients were doing the matching work themselves and we’d be equipping them with information to make a great decision, we’d be able to deliver our service in a far less labor-intensive way than before - with far better economics and better, more informed matches for clients at the time time.

And those clients would 'fall in love' with the talent they discovered organically

By the time clients reached out to them, the idea was that they were excited enough about this particular freelancer that they wanted to hire them and only them - they wouldn't just be looking for 'a content writer', they'd want one specific person whose work they'd fallen in love with.

And probably make hiring decisions based on what really matters - what someone can actually do for them

This approach encouraged people to base their hiring decision around the impact someone might have on them - not on all the superficial things like job titles, degrees, and more that bias peoples' hiring decisions today.

It would also mean that we wouldn't need human effort to help clients hire

Given we were equipping clients to make the decisions themselves, we wouldn't need to constantly hold their hands throughout the hiring process - we were trying to make it so that they'd be pulled through it by their enthusiasm about the person they discover, instead of us having to push them.

Because there was less of a 'human variable' on our side, it would've scaled a lot better

Given every hire wasn't dependent on human effort to happen, this approach could've scaled a lot easier. We could in theory have had 100s of hires per month per account manager, rather than 20-30 with our previous approach.

And would have far better economics as a result of the reduced costs

Given that we wouldn't need human input to make hiring happen on our platform, we'd potentially have far better economics as a result of the reduced costs to deliver a hire.

And the work that resulted from these relationships would also be and higher-level

Given the relationships sparked would be based on more higher-level requirements - people who found stuff while exploring ideas - we felt that the work that resulted from these relationships would also be more higher-level.

And the process would likely work for all the best talent - given they wouldn't have to apply for jobs

Because people wouldn't have to apply for projects, we felt that this kind of approach would in theory work for anyone - even the best of the best talent.

Why our new version failed

Maybe because we're still building in a bad market, maybe because we were still not building something that we want to exist in the world, or some other reason.

Why did our new version not work?

We shipped 3 distinct versions of our new product with many little iterations in between.

For each, we onboarded 300-500 users and collected deep feedback on them through user interviews.

Between each version, we worked hard to fix the issues with the previous version - shipping numerous major product updates, positioning changes, tweaks, content reformats, and more.

Our north star was the percentage of clients who actually reached out to a freelancer as a product of our usage - if enough clients were ultimately discovering talent that they wanted to hire, that meant our product was, at its core, working. We felt that 5% of people discovering talent was a good starting point to shoot for that we could then improve on.

For our first version, 0% of clients discovered freelancers that they reached out to - apart from a few who were aided manually by our team. A complete failure.

For our second version, we made a bunch of big changes to the product and positioning, and, as a result, c. 1.4% of clients who signed up reached out to someone. A significant improvement!

For our third version, we worked for almost 3 months, transforming many elements of the product to try to deliver a huge improvement over version 2. However, we only saw a marginal improvement, with only 1.7% of users who signed up ultimately finding someone.

While it's difficult to tell what actually was the core reason behind it not working well enough, below are a few of the possibilities based on our data and user interviews:

The quality of the content wasn't good enough

While there are a bunch of problems that surfaced on our feedback calls, the no. 1 problem was likely the quality of the content.

Basically, users have so many other better options of where to find content - blogs, LinkedIn, Twitter, Tiktok, etc. - and our content didn't reach the bar they have for spending time on it. I don't think that it was incrementally off, but rather an order of magnitude.

We optimised for speed and ease of creation, not quality - which isn't acceptable in a world where there's so much free great content available and other ways for people to spend their time.

We did this because - with our approach - we needed to create content at a reasonably large scale for fairly cheap.

It's also because it's ultimately very hard to create great content - this is why editorial houses, newsrooms, etc. exist - to moderate, control, and produce content that hits a consistently high bar.

We did this because we thought that we could leverage the freelancers to create a big enough body that would be good to explore in and itself - even if the individual pieces aren't excellent.

However, our finding was that the individual pieces need to be worth the readers' time, in and of themselves.

The idea is superficially attractive but it's not something people want in reality

As per the above, we have no problem attracting people to sign up for this and they were mostly good people.

However, the fact that their interest didn't convert into action might indicate that it was superficial - that they are curious about the concept in theory but don't really want it.

Despite improvements, the content UX was still hard to digest.

We made a bunch of efforts to improve how easy the content was to digest.

While we improved the UX of the top of the content greatly and extracted the key pieces of information from it to make it easier to digest, the body remained a long, hard-to-ready chunk of text. I think that this was probably a factor, but what the content actually contained was likely a bigger one.

A bunch of more minor UX issues degraded the experience

Users had a bunch more feedback on different elements of UX. While they probably degraded the experience a bit, it doesn't feel like they were critical.

Positioning issues stopped people from understanding it properly

We toyed around with different angles for the positioning based on our understanding. While they worked in terms of getting users, it's possible that the stuff that attracted people wasn't aligned with what the product could deliver.

The fundamental idea just doesn't make sense

Again, related to the above, it's possible that the idea underlying what we're doing just doesn't make sense - that people won't discover freelancers based on the content in a way that's capturable by a platform.

Some other lower-probability reason

There are obviously a bunch of other contributing factors, including potentially:

- The quality of talent wasn't good enough

- We had bad timing

- Marketers don't care enough to engage with new ideas

And why are we choosing to shut it down?

We needed to get to be either investible or profitable in under six months. This dramatically reduced the number and attractiveness of options.

The 3 main options we considered were:

1. Continue to iterate in the hopes that we have a breakthrough:

We considered continuing with another new version in the hopes that it'd deliver the kind of improvement that we needed - we thought that maybe we just needed to keep going and persist.

However, given how small the impact of all our improvements over the last version, we had low confidence that we could make a significant improvement in the time we need.

2. Change how we were doing things to dramatically improve the quality of the content

We considered fixing the content quality issue by scraping the best marketing content from elsewhere instead of using our own.

For example, we would scrape content like this brilliant article about building a SaaS brand from the former VP of Marketing at Lattice and feature it on our platform.

However, in solving one problem, it would also cause many more - the talent would be less engaged, the content might be too inconsistent, etc. - while we could probably get a v.1 in 1-2 months, it felt highly unlikely that we would have enough time to solve these big problems.

3. Pivot to artificial intelligence

We considered a dramatic pivot into AI. Given the dynamics of that space, giving people access to talent didn't make sense, but it felt like giving them access to fine-tuned models that the talent produced might.

We explored basically building a marketplace for these fine-tuned models - a place where people can add and explore different AI capabilities that others have produced using large language models.

However, we felt that, as with the other options, we wouldn't have enough time and money to get to either being investible or profitable with this idea.

Secondly, in retrospect, it felt as though jumping into Advisable without proper thought because I wanted to not be doing nothing was my own critical meta-error.

Given this, it felt like jumping into anything new - even a potentially good idea in a hot area - would be a bad decision made for the wrong reasons.

What are the reasons underlying our failure?

While the above are the reasons why that specific version didn't work, below is a list of potential factors underlying our failure.

Again, they are in order of how likely I think it was that they were the critical factor and as before, you can click on each to get more detail:

We're in a market where there aren’t proven large, successful businesses that offer substitutable services (aka: a bad market)

However, you define us, we're probably not in a great market.

If you consider us a freelance marketplace, the largest businesses are sub-$2b market-cap and mediocre/floundering.

If you consider us a marketing services business, the largest businesses are few hundred person agencies. There are also agency roll-up businesses like WPP that are larger but it's probably better to think of them as multiple businesses than single ones - more private-equity plays than companies.

I don't think that it's impossible to succeed in such conditions, but I do think that you probably need to revolutionise the industry you're operating in - and to do this, you probably need to understand the industry to an insane level of depth - covered below.

We tried to build a revolutionary product, but we're not the people we're building for nor are we building something that we wish existed in the world

As per the above, this is probably a space that is unlikely to produce a great company unless they're taking a revolutionary approach - there have been decades for a well-executed, incrementally-oriented business to build a great business in this market and they haven't.

As a result, after our pivot, we were trying to build a revolutionary product - not one that does what they’re already doing faster, cheaper, or better, but does something completely new - with the hopes of changing peoples’ behaviour entirely.

However, it feels likely that, in order to build a revolutionary product, you need to be building for yourself - building something that you personally want to exist in the world because you want to use it - not just something that intellectually makes sense.

This is because you need to understand the space you're trying to transform to a very high degree in order to know how to transform other peoples' behaviour and inspire change. This is probably practical - knowing all the details of how to get it right - but also reputational - to inspire early adopters with your legitimacy.

We simply weren't this. We were very intellectually engaged in solving the problem but weren't building something that we wish existed. While it's hard to point a finger at what the effects of this might have had, there were likely a million little ones, and a number of big reasons why it just meant that our execution wasn't good enough. This doesn't preclude the fact that we could've gotten lucky in spite of this (especially had we been in a better space!) or maybe persisted until something worked.

We didn't understand our customers well enough

Related to the above, we didn't understand our customers well enough.

This is a tricky one however as given the fact that we were trying to build something that we hoped that would want but not necessarily something that they were asking for - we weren't just building to solve a problem that they had.

This meant that we were able to talk to them about how it would ideally work for them and get feedback from them on our attempts, but they probably wouldn't be able to direct what we do in the same way that they could if we had we building a more incremental solution - doing something they already do faster/cheaper/better.

In any case, we didn't understand them well enough to build something transformative for them.

It's very hard to deliver a consistent, high-end service when a key variable is as inconsistent and unmeasurable as marketing talent

I think the only businesses that manage to deliver a high-end service with a variable as inconsistent as talent, have some combination of the below:

- Reasonably quantifiable/objective skills: like software development or management consulting - quality measurable to a reasonable degree by tests or pedigree.

- Amazing margins: to allow for a lot of work and oversight to ensure that the service is delivered consistently.

We needed to take a far more service-oriented approach

Most successful high-end services businesses obviously take a very service-oriented approach.

I have no doubt that taking a more service-oriented approach (as we were before) could've been a good business, but also think it would almost certainly have been inherently limited by this approach - it would never have been a great business.

Some other lower probability reasons

While the above are probably the main reasons, below are some low-probability reasons I wouldn’t exclude as having also been contributing factors underlying our failure:

- Our approach hinged on being able to create great content at scale, which is very difficult.

- We weren't fast enough in executing

- I wasn't competent enough in leading the company

- We gave up too early

- We shouldn't have changed direction in the first place

- There isn't a good enough incentive for great people to share their work

- We didn't have enough time

- Marketers don't care enough to engage with new ideas

- Marketing isn't a dynamic space and matters less and less

- We were too late to the market generally

- We had bad timing given the economic situation

Reflections

What would I say to my past self? Was it just a bad idea? What are the members of the team going to do now?

"If you could communicate non-situation-specific information to your past self, what would it be?"

This is actually a very tricky question - in part because past me had a lot of bullshit that would've prevented him from seeing the truth.

But I'd hope that, given he was hearing from his future self, he'd take time to consider the following question:

"What's are fundamentally good reasons to build a company?

Why try building something in the first place? There are good and bad reasons for this. Bad ones include ego and arrogance and wanting to fill space - as had happened with me.

I'd hope that, upon pondering it, past me would reach the conclusion that I have now, that there are roughly 3 good reasons:

Because you feel that you can do something that people are paying others for significantly faster, cheaper, or better in some meaningful way.

If it can be a great business, there are almost certainly other good businesses that offer a substitutable product to the market - it might not be obvious what this substitutable product is, but they do mostly exist.

Because you're truly building something that you wish existed in the world - something that people like you will love using.

If it's something you really wish existed in the world, you'll be unable to stop thinking about it and won't need external validation to build up conviction and commitment.

Ideally, a combination of both of the above.

The golden ticket - something you wish to exist, that also is offering something that's substitutable to one that people pay a lot of money for today in some way.

I'd hope that, upon really considering this, past Peter would've figured out that maybe this isn't the best way to spend 4-5 years.

"Do you still think that what you were pursuing was a fundamentally good idea?"

While I don't believe that our direction would've delivered what we were pursuing and think it's possible that we weren't the right people to do it, I still believe that our fundamental idea makes sense.

I believe that a world where everyone is sharing their best work for others to learn from would be better for everyone. This already happens in areas like software development and design to an extent, and it really helps elevate these spaces.

I believe that the people who are learning from the work of others would improve best practices and innovation in the space for everyone.

I believe that, in this world, great, collaborative relationships would be formed as a product of the openess, which would make sharing the content in the first-place worthwhile.

I believe that the relationships formed would be unlike the low-level, dictatorial relationships formed on the freelance marketplace today - they'd be collaborations between partners and peers.

I believe that the work accomplished from these collaborations would likely be far more visionary and brilliant than most work that happens today and would also elevate the space further.

I believe that, if someone figured out to do all of the above, there's a very good chance that it would work and there's a very good chance it could be an incredible, industry-defining business.

That said, I do have doubts that it might be possible to capture the above as a business - it might be more of a grassroots philosophy. It also might need AI to advance further in order to enable people to create consistently amazing content at scale in a way that isn't labourious.

It would also probably need someone who deeply understands the space they're operating to figure out how to deliver it in a way that made sense for people and inspire them to get on board. They'd also probably need to be part of the space to spur this transformation from the inside.

But I do believe that it's probably possible and it would be a better world in which it happened - despite our failure in delivering it.

"What is the team going to do now?"

While I made many mistakes with Advisable, one thing I couldn’t be prouder of is the team we built.

Having worked for several reasonably successful startups before, I had a fairly high-talent bar going into Advisable. Throughout our time, I fought to keep it up, and to build an environment that great people would want to work in, and I think was mostly successful!

What saddens me most about shutting down Advisable is that I know there's another world in which this same group of people had built a truly great business with an impactful, unique product. It would also have been a great place to work! That's how good these people were.

While shutting down a company involves a lot of worries and uncertainty, one thing I’m not worried about is the bright future that each of them has.

I know that they’ll have no trouble finding great opportunities and not all of them are actively looking. That said, if you or someone you know wants to be the lucky one to work with them, now is your chance to shoot your shot!

You can check out a full list of them here.

"Any parting words?"

Thank you for asking!

I would say that not every great adventure that you go on with great people, ends up where you'd hope it would!